Prescription drug shortages: An unfolding crisis

Niraj Mehta, Chemistry PhD Student, Stanford University

nirajm@stanford.edu

In November 2022, three FDA inspectors paid a visit to the sprawling manufacturing facility of Intas Pharmaceuticals, an Indian pharmaceutical giant. Located an hour south of Ahmedabad, in the western state of Gujarat, this plant was responsible for producing half of the U.S. supply of the crucial cancer drug, cisplatin.

What the FDA inspectors stumbled upon at the facility were pervasive issues, from shredded safety documents drenched in acid to a series of quality assurance failures. Intas responded by halting its production to address these concerns. A few months post this suspension, a crisis began unfolding in America- the US had suddenly lost fifty percent of its cisplatin supply. With up to 10% to 20% of all cancer patients receiving cisplatin or drugs like it, the impact was felt immediately. Oncologists were compelled to explore alternative treatments, and hospitals were frantically searching for supplies, potentially impacting hundreds of thousands of patients.(1)

Over the preceding year, cisplatin has become emblematic of the growing supply issues surrounding generic drugs in the United States. But since then, the scarcity spectrum has broadened, affecting availability of various medications ranging from children's acetaminophen to antibiotics and ADHD medications.(2)

So why are some of our most important medicines, the cornerstone of our health systems, at risk of disappearing from our shelves? In this article, I will explore the myriad facets of this looming crisis. I will focus on generic drugs, the backbone of the American health system, shedding light on the economic and regulatory factors that are pushing our pharmaceutical supply chains to their limits.

What are generic drugs, and why are they important?

Generic drugs are essentially cheaper versions of brand-name drugs. They are incredibly important to the US healthcare system – accounting for 90% of prescriptions in the U.S., generic drugs save up to $400 billion in drug costs every year.

Drug manufacturing has become increasingly offshored

Generics are a large business. In 2022, the US generic drug market was valued at $86 billion.(3) In the early 2000s, international pharmaceutical manufacturers, particularly in India, started seeing an opportunity here.

Driven by large domestic markets and the availability of cheap labour and talent, Indian companies had long serviced pharmaceutical demand within their domestic markets. But in the early 2000s, a key governmental initiative, United States President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), introduced by the Bush administration, inadvertently opened the doors for Indian pharmaceutical manufacturers to turn to the US as a new market.(4)

PEPFAR, originally designed to combat AIDS in Africa, facilitated an expedited review process that allowed Indian manufacturers to get FDA approval to produce and supply antiretroviral drugs for Africa. But eventually, these newly obtained FDA approvals, although in principle meant for Africa, also allowed Indian pharmaceutical companies to start exporting to the U.S. market. This began a boom in the Indian pharmaceutical industry, where a growing number of manufacturers started building manufacturing facilities for producing generic drugs meant for the US.

Powered by years of domestic manufacturing know-how, cheap labour and talent, these Indian manufacturers started outcompeting their American counterparts on cost.

To illustrate , let’s look at applications for generic drug approval submitted over time in the US (i.e. ANDAs) – in 1990, approximately 50% of these applications were submitted by U.S. companies, while only 15% originated from India. Fast forward to 2012, and U.S. firms accounted for just 30% of filings, while Indian submissions had escalated to 40%.(5)

With an increase in generic manufacturing competition, and a new supply base taking shape in India, patients in the US started enjoying the benefits of improved generic accessibility – the share of generic drugs as a total share of drugs sold in the US went from 50% in 2005 to nearly 90% in 2020.(6) The price of critical drugs like the cholesterol lowering Lipitor went from $3.29 (brand-name) to $0.08 for the generic equivalent, affording staggering savings of 98% to patients and insurers.

Simultaneously, however, India was witnessing a surge in competition to supply this large and growing market – an ever-larger number of players were now entering the arena. Just over the past decade, the number of Indian companies filing for new generic drug applications went up by five fold, now totalling around 25.(5)

A winner takes all scenario – a competitive market and the Hatch-Waxman Act

As competition on the supply side was growing with a growing number of manufacturers, pricing pressures began to emerge. When there are fewer competitors for manufacturing a generic alternative to a brand-name drug, generic prices can be kept at between 30% and 90% of their brand-name competitors.(7) But as the number of generic manufacturers increases, drug prices are increasingly commoditized, driving the manufactures’ margins downwards.(8) (Figure 1)

Figure 1 The ratio of generic price to branded price as a function of the number of generic manufacturers for that drug. Figure from ref. (7)

So, to contend with losing out on margins and volumes to competitors, several generic manufacturers started focusing on producing drugs that had fewer competitors, and therefore, yielded higher margins.(8)

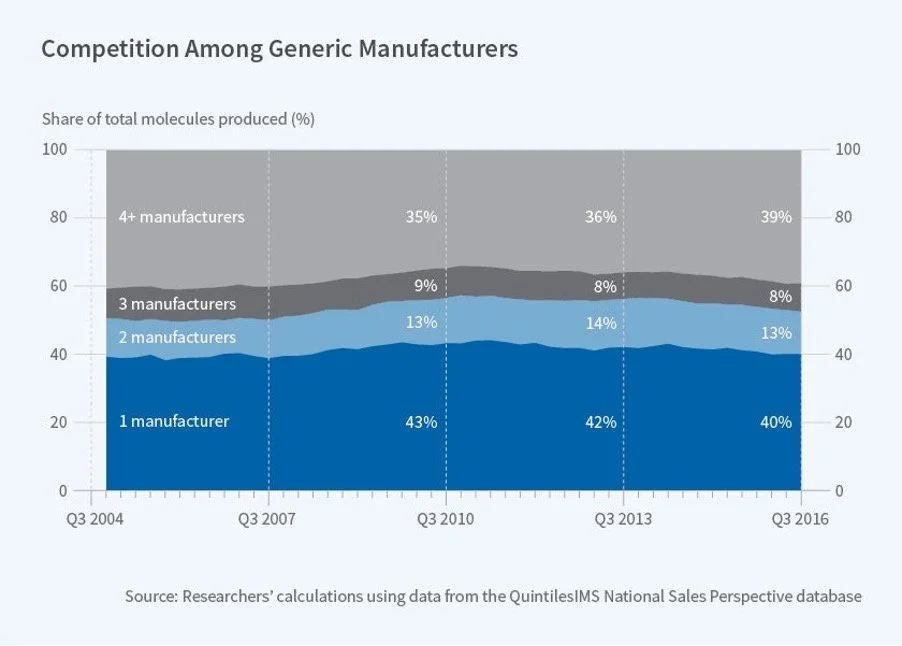

This was a problem – market forces systematically were discouraging multiple manufactures from producing the same drug, leaving 40% generic drugs with only one supplier (Figure 2).(8)

To make things worse, a crucial piece of policy was further disincentivizing generic drug competition – the Hatch-Waxman Act, enacted in 1984 by Congress to regulate generic drug competition, provides the first generic drug to enter the market a 180-day period of exclusivity, during which no other generic competitor can launch.

This exclusivity period is crucial for overall profitability for the manufacturer allowing the first generic manufacturers to be the sole suppliers for that generic drug and, consequently, to command larger volumes and set high prices for their products.

Although it's designed to promote competition against brand-name drugs, paradoxically, the Hatch-Waxman Act appears to further limit the number of suppliers and constrict competition. In effect, the first generic entrant secures a large piece of the pie, creating a winner-takes-all scenario.

Figure 2 Share of Molecules by Number of Generic Manufacturers. About 40% of generic drugs have only one manufacturer. Figure from ref.(9)

So, numerous U.S. drugs had been reliant on a limited number of suppliers. But this fragile supply chain was about to be delivered its harshest blow – and this time, it came from within the US.

Extensive consolidation amongst buyers

Generic manufacturers typically don’t sell directly to hospitals or pharmacies; instead, sales are facilitated by intermediary wholesalers in the US. Wholesalers typically procure their drugs from manufacturers – manufacturers list prices for the drugs they make to wholesalers, and wholesalers typically pick the supplier offering the lowest price. These wholesalers in turn sell onwards to pharmacies, hospitals, nursing homes, etc.

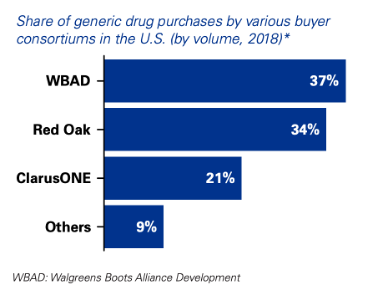

The past decade has seen unprecedented consolidation among these buying consortia, through either acquisitions or joint ventures.(10) A trifecta of buying groups— Red Oak Sourcing, Walgreens Boots Alliance and ClarusOne— have come to dominate. Together, these top three pharmaceutical buyers account for over 90% of wholesale generic drug sales occurring in the US (Figure 3) (11,12).

Figure 3 Consolidation amongst wholesale buyer groups in the US. Figure from ref. (13)

This consolidation has afforded the wholesale buyers massive bargaining power, amplifying price-based competition amongst manufacturers. Bidding cycles have become more frequent, further lowering prices for generics.(14)

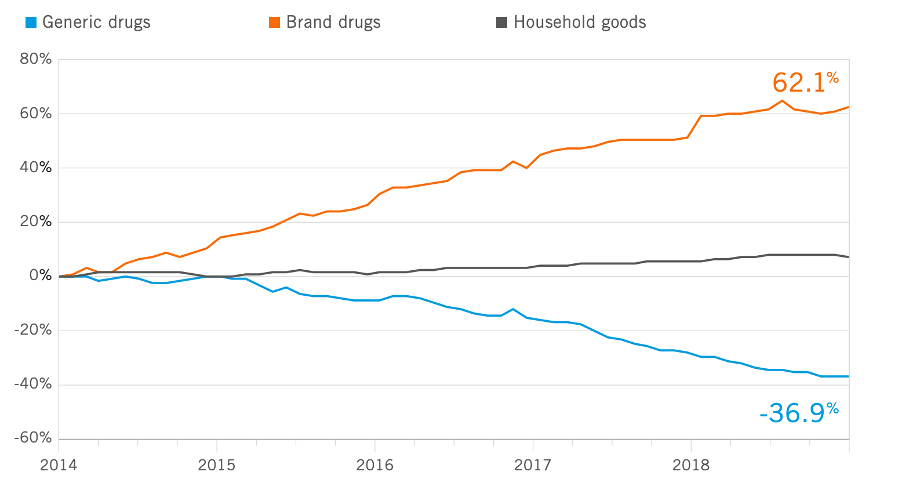

Figure 4 Generic drug price index shows how brand-name drugs have gotten more expensive, and generic drugs have gotten cheaper. Figure from ref. (15)

For generic manufacturers, consolidation and amplified bargaining power amongst buyers meant that now they had to operate with diminished influence in their principal markets. This, combined with intense competition, significantly affected product margins – just between 2016 and 2019, product margins dropped by nearly 40% (Figure 5).(13) Even for generic drugs that won 180-day exclusivity, manufacturers failed to secure high prices as the pressures exerted by consolidated buyers limited them to small fractions of branded drug prices.

A precarious market environment resulted; manufacturers, despite significant capital investments, now are left with no long-term guarantees or certainty of demand. Several generics manufacturers straight up exited the US market– they were, by 2016, delaying or cancelling launches for nearly 40% of generic drugs that they received FDA approval for.(13)

In an already brutal industry that often sees razor-thin margins, generic drug prices were now entering a race to the bottom.(14)

Figure 5 Margins reported by generic drugmakers over time. Figure from ref.(13)

Recap

So to summarize, we currently face a generic drug supply chain teetering on the brink of collapse:

It’s massively offshored, with 40% of the supply originating from India. Competition has dwindled, and most drugs only have 1-2 manufacturers.

The US generics market environment is unfavorable, growth has stagnated

For the suppliers that remain, margins for products on the market are often tightly squeezed by intermediary buyers

So, what lit the fuse on this precarious situation? It turned out to be the FDA’s inability to inspect manufacturing units and the quality issues that ensued at certain pharmaceutical companies.

Compromised Quality + Inadequate FDA Oversight = a brewing storm

Purchase orders by wholesalers in the US are awarded to manufacturers supplying at the lowest prices. In theory, this shouldn’t affect American patients, since the FDA has the mandate to ensure quality for all drugs entering the US. However, here’s the catch – the FDA is chronically underfunded and doesn’t have the capacity to inspect most foreign manufacturing sites. In 2022, the FDA only inspected 6% of overseas manufacturing sites.(16)

So in other words, the industry environment for generics manufactures is brutal— margins are squeezed, and the manufacturer selling at the lowest price is winning. But nobody is really checking product quality.

In practice, what this signals to manufacturers is that it’s possible to cut corners on drug quality and get away with it.

This has unfortunately been discovered repeatedly again over the past few years. In her book A bottle of lies, author Kathleen Eban chronicles how systemic fraud, compromised quality, and dangerous practices dominated at key generic drug manufacturers like Ranbaxy, showing how poor quality control and regulatory oversight is becoming a problem within the generic drug industry.

The recent closure of the Intas cisplatin plant, or the numerous revelations about compromised manufacturing practices at Ranbaxy aren’t isolated incidents. Today, about 26% of prescription drugs sold in the US are being supplied by companies that have received warning letters from the FDA.(14)

These warning letters are issued upon non-conformance to manufacturing standards, and do not necessarily indicate compromised product safety or quality. Nonetheless, a growing number of manufacturers have ceased production for the US following FDA warning letters, as the cost of compliance, against a backdrop of already diminishing margins, becomes too steep to warrant continued manufacturing for the US market.

It's not about a few bad players, but misaligned incentives within the industry

To emphasize, the problem is not about a few bad players compromising the system– instead, the story is about how a difficult market environment and paradoxical incentives for manufacturers combine with insufficient regulatory oversight to ultimately reward the wrong players. Quality-focused manufacturers simply have little systematic incentive to win. At the end of the day, the manufacturer offering the lowest price wins.

Intas or Ranbaxy may have come as a revelation to the broader world, but insiders within the industry long understood that a race to the bottom was making the US market unattractive, with lowest-price bidding contracts compromising quality for price.

And the worries don’t end there – drug supply chains are highly concentrated at source

If a 40% concentration of pharmaceutical manufacturing in India seems profound, brace yourself for an even more staggering reality—China is the ultimate architect behind the majority of the world’s Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). These are the key active ingredients within drugs. Even India, the colossal supplier of medicines to America, relies on China for a whopping 70% of its API needs.(17)

There is a veil of secrecy around API manufacturers. These entities operate without FDA oversight, their identities closely guarded by drug-makers as trade secrets. Often, it’s unknown where an API was sourced from. A recent estimate suggests that up to a third of APIs integral to U.S. pharmaceuticals are only have one supplier(17). This means that even when multiple manufacturers are involved in producing various drugs, they could all be tethered to a single source for their APIs.

This unveils a new dimension of vulnerability in drug supplies. Geopolitical events or disruptions like the ones caused by COVID-19 have exposed the fragility of our reliance on these singular entities, threatening the continuity of drug supplies globally. The whole world could be dependent on isolated factories for the entirety of its medicinal needs – a reality that underscores the urgent need for transparency, diversification, and robustness in our pharmaceutical supply chains.

Why didn’t the FDA pre-empt these shortages?

Today, 99% of hospital pharmacists are reporting drug shortages.(18) A third of them have started to anticipate shortages and stockpile supplies, or ration, change or delay care for patients dependent on medicines in short supply, according to an American Society of Health-System Pharmacists survey.(18) This is the highest rate of drug shortages reported in recent US history.(19)

But why didn’t the FDA pre-empt the fragility of the cisplatin supply? The FDA maintains a list of drugs in short supply – as of Sep 2023, 143 drugs were listed to be in short supply by the FDA(20). However, the FDA doesn’t list a drug in shortage until it has confirmed that “overall market demand is not being met.”(21) In other words, it’s only after supply fails to meet demand that the FDA lists the drug to be in short supply. As we saw, countless other drugs are in similar position – with only a few manufacturers dominating the total US supply for that drug. (Figure 2)

Solutions?

The current state of the generic drug industry reveals a stark misalignment between market incentives and the interests of patients in the U.S. The industry is entrenched in a detrimental race to the bottom, on top of which the FDA struggles with ensuring consistent quality due to its limited capacity. This environment allows manufacturers who produce for less to potentially compromise on compliance costs, creating a skewed and unfair incentive structure within the generic manufacturing space. Recognizing these fundamental truths is crucial, and it is in this context that I’m making the following suggestions to realign market incentives with consumer interests and uphold the integrity of the generic drug industry.

Long-Term, Large-Volume Contracts for manufacturers: First, we must recognize that declining profitability for manufacturers is at the heart of the ongoing problems. Making the US market more lucrative for them should be a priority. Establishing long-term, large-volume contracts would provide manufacturers with the stability and assurance needed to invest in high-quality production, ensuring the sustained availability of essential, high-quality generic drugs in the market. Tying these contracts with additional quality stipulations could further link financial incentives with quality enhancements and could improve overall drug quality (for example, this could include compliance with the FDA’s recently proposed Quality Management Metric, QMM, which is a voluntary program that involves rating-based assessments of manufacturing facilities, as recommended by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists). This could manifest as guaranteed volume, fixed-duration contracts with generic drug manufacturers, fostering a conducive environment for the sustained production of high-quality generic drugs.

State-Owned Generics!? (Or non-profit generics): Provocative as this may sound - the adoption of state-owned generics could offer a stable and reliable supply of essential medications, mitigating risks associated with over-reliance on external manufacturers, thus contributing to overall supply chain resilience. While the concept of state-owned generics manufacturing units in the US may seem unconventional, it has historical precedent, with entities like MassBiologics in Massachusetts producing and distributing vaccines and biologics for over 125 years. Legislative proposals introduced by Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Sen. Jan Schakowsky are exploring this avenue. More recently, an exciting non-profit model has emerged for generic manufacturing and distribution – CivicaRx, a non-profit launched in 2018, sources generic drugs from manufacturers that it vets for quality, and builds up long-term inventories for those drugs, which it then directly supplies to hospitals under long-term contracts.(22) This model could provide hospitals long-term supply certainty while also rewarding quality.

Better funding for the FDA: This one goes without saying – the FDA plays a pivotal role as the sole gatekeeper to quality in the pharmaceutical market. But it faces glaring resource constraints. When the FDA approves multiple products with varying quality levels, the prevailing contract winners are those offering the lowest prices, not necessarily the highest quality.

Summary

Enormous pricing pressures are pervading the generic pharmaceutical industry, rendering the economics of making generic drugs unfavorable. The industry is teetering on a precarious balance where suppliers with the lowest prices are triumphing, but quality is being overshadowed and unrewarded. A major contributing factor is the incapacity of the FDA to adequately assess the quality of products, allowing the industry to systematically reward players concentrating on price, not quality. The fallout of this paradigm is an escalating number of drugs compromised on quality. This issue transcends the challenges associated with offshoring; it is the manifestation of flawed systemic market incentives. The generic drug industry is pivotal, having saved billions in healthcare expenditures and forming an integral component of the American healthcare narrative. Thus, it is imperative to contemplate strategies to bolster competitiveness for manufacturers in this industry and enhance regulatory oversight. The goal should be to recalibrate the marketplace to reward the right incentives, ensuring both the quality and affordability of generics are upheld.

References

1. USA TODAY [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 29]. As drug shortage list grows, many hospitals face tough decisions on rationing care. Available from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/08/10/drug-shortages-hospitals-ration-care/70566227007/

2. How the Shortage of a $15 Cancer Drug Is Upending Treatment - The New York Times [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/26/health/cancer-drugs-shortage.html

3. US Generics Market - Evolution of Indian Players - IQVIA [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/locations/india/library/white-papers/us-generics-market-evolution-of-indian-players

4. NPR [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Sep 30]. The Generic Drugs You’re Taking May Not Be As Safe Or Effective As You Think. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/05/16/723545864/the-generic-drugs-youre-taking-may-not-be-as-safe-or-effective-as-you-think

5. Chemical & Engineering News [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 29]. 30 Years Of Generics. Available from: https://cen.acs.org/articles/92/i39/30-Years-Generics.html

6. The Use of Medicines in the U.S. 2022 - IQVIA [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/the-use-of-medicines-in-the-us-2022

7. Grabowski HG, Ridley DB, Schulman KA. Entry and competition in generic biologics. Managerial and Decision Economics. 2007 Jun 1;28(4–5):439–51.

8. NBER [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 30]. Competition in Generic Drug Markets. Available from: https://www.nber.org/digest/nov17/competition-generic-drug-markets

9. NBER [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Competition in Generic Drug Markets. Available from: https://www.nber.org/digest/nov17/competition-generic-drug-markets

10. Fein AJ, Ph.D. The Big Three Generic Drug Mega-Buyers Drove Double-Digit Deflation in 2018. Stability ahead? (rerun) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.drugchannels.net/2019/07/the-big-three-generic-drug-mega-buyers.html

11. 2019 Report: The Role of Distributors in the US Health Care Industry | Deloitte US [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/the-role-of-distributors-in-the-us-health-care-industry.html

12. Generic drug industry calls on FTC to dig into monopsony power among buyers, PBMs [Internet]. Endpoints News. [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: https://endpts.com/generic-drug-industry-calls-on-ftc-to-dig-into-monopsony-power-among-buyers-pbms/

13. Generics 2030: Three strategies to curb the downward spiral [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Available from: https://kpmg.com/us/en/articles/2023/generics-2030-curb-downward-spiral.html

14. Sardella A. US Generic Pharmaceutical Industry Economic Instability. Washington University Olin School of Business Center for Analytics and Business Insights. 2023;

15. CVS Health Payor Solutions [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 3]. 2018 Drug Trend Report. Available from: https://payorsolutions.cvshealth.com/insights/2018-drug-trend-report

16. FDA Only Inspected 6% of Foreign Drug Manufacturing Facilities in 2022 — ProPublica [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.propublica.org/article/fda-drugs-medication-inspections-china-india-manufacturers?utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=socialflow

17. Socal MP, Ahn K, Greene JA, Anderson GF. Competition And Vulnerabilities In The Global Supply Chain For US Generic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Health Affairs. 2023 Mar;42(3):407–15.

18. SEVERITY AND IMPACT OF CURRENT DRUG SHORTAGES, June/July 2023 [Internet]. ASHP; Available from: https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/drug-shortages/docs/ASHP-2023-Drug-Shortages-Survey-Report.pdf

19. Highest 10-Year Drug Shortage Rate Reported [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/highest-10year-drug-shortage-rate-reported

20. FDA Drug Shortages [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm

21. Allen A. Drugmakers Are Abandoning Cheap Generics, and Now US Cancer Patients Can’t Get Meds [Internet]. KFF Health News. 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Available from: https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/drugmakers-are-abandoning-cheap-generics-and-now-us-cancer-patients-cant-get-meds/

22. Yong E. The Atlantic. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 1]. The Cancer-Drug Shortage Is Different. Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2023/06/cancer-drug-market-dysfunction-supply-shortage/674512/

About the author

Niraj Mehta

Niraj is a PhD candidate in the Department of Chemistry. Prior to Stanford, he studied Chemical Engineering at UCLA. Inspired by Nature’s tremendous ability to produce molecules that modulate biological processes & treat human diseases, he works in the Sattely Lab at Stanford, where he employs multi-omics approaches to understand & engineer the production of therapeutic plant natural products. He has a keen interest in translational research & drug development and biotech venture capital. Niraj is a board member at the Stanford Biotech Group, and previously served as president of the group (2022-23).